The Observer reported this weekend that high-street clothing chain H&M is being accused of buying from clothing suppliers that may be using Uzbek cotton. Cotton in Uzbekistan is notorious for being produced under a government-organised labour programme which reportedly sees children taken from school and forced to pick cotton for months at a time. H&M says it bans Uzbek cotton from its supply chain.

There's an odd paragraph at the end:

"Concerns about the use of Uzbek cotton have led to questions being asked of Peter Lilley, the former Tory trade secretary who heads the Uzbek-British Trade and Industry Council, which promotes the Uzbek Cotton and Textile Fair....In an emailed reply, Lilley said the council followed Foreign Office guidelines and its main role was "to broaden trade and investment between the UK and Uzbekistan", not promote cotton."

It's a weird quote, and a not-quite denial. But whatever Mr Lilley may have said to the Observer, his Uzbek-British Trade and Industry Council (UBTIC) has definitely promoted Uzbek cotton. Over the summer I was passed an email sent out by UBTIC to its members - including prospective UK investors in Uzbekistan - carrying Peter Lilley's signature, and inviting them to come to Uzbekistan and, um, sign cotton contracts. Back to that in a minute.

Why all the fuss? We all basically know that a lot of unpleasant things go on in the rag trade. Across the textile industry, child and sweated labour remains far too prevalent. But there are fairly few instances of textiles actually being made using child slave labour.

One exception is Uzbekistan's cotton industry, where an export-hungry government issues ever-growing cotton production quotas each year, and then fills them by forcing both adults - from teachers to factory workers - and children, reportedly as young as 10, to leave their schools and workplaces to work in the fields during the cotton harvest. ILO observers are banned from the country during the cotton harvest, and activists seeking to expose forced child labour have been arrested and detained. The 2012 harvest has just finished, and Uzbek activists report that international pressure has led to the youngest children being removed from the fields - but allege that teenagers are still being sent out and required to pick 60kg of cotton a day. Even the U.S. government, sometimes conservative in calling out Central Asian states on their human rights records, has said it's getting worse:

"Domestic labor trafficking remains prevalent during the annual cotton harvest, when many school-age children as young as 10 years old, college students, and adults are victims of government-organized forced labor. There were reports that, during the cotton harvest, working conditions included long hours, insufficient food and water, exposure to harmful pesticides, verbal abuse and inadequate shelter. The use of forced mobilization of adult laborers and child laborers (over 15 years of age) during the cotton harvest was higher than in the previous years."

|

| Girl harvesting cotton in Kashkadarya, Uzbekistan, October 2011 (Anti-Slavery International) |

That's why dozens of usually unsqeamish high-street clothing chains, from Wal-Mart to Zara, refuse to source Uzbek cotton. The French contact point of the OECD says that clothing companies that buy Uzbek cotton picked by forced labour and children may be violating OECD rules on business and human rights.

So: everyone happily agrees that we shouldn't buy Uzbek cotton until they stop using child slaves to pick it.

Everyone, that is, except UK Trade and Investment (UKTI), a British government body under the joint aegis of the Foreign Office and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. UKTI is tasked with promoting British business overseas. By and large, this seems like a good thing. But UKTI also works to promote overseas business to the UK - including its cheerful sponsorship of the Uzbek-British Trade & Industry Council (UBTIC), a trade promotion outfit chaired jointly by Peter Lilley MP and the Uzbek Trade Minister. Mr Lilley told me he is unpaid for his UBTIC work, but has "a part-time assistant". Despite UBTIC falling under the auspices of UKTI - a government body - Mr Lilley also said that it did not have to get UKTI's approval for any activities or communications; although he "now refer[s] anything likely to be contentious".

And so to Mr Lilley's email to UBTIC members, which I've reproduced below. As you can see, it invites them to register for the 8th International Uzbek Cotton and Textile Fair in Tashkent, where

"participants will enjoy an opportunity to sign contracts for Uzbek cotton, set up long-term cooperation in cotton trading, as well as to be familiar with the quality of Uzbek cotton and the latest innovations in trade and logistics. Moreover, during the Cotton Fair “round tables” and bilateral negotiations between Uzbek cotton exporters and consumers will be organized."

I asked Mr Lilley, in the light of this email, whether UBTIC is involved in promoting Uzbek cotton. He replied "No - as explained" [in his quote to the Observer]. I'm not really certain how this is explained, since his email is pretty clear. It carries the logo of UKTI, and also handily attaches an invite and registration form for the Tashkent Cotton Fair. That'll be for cotton that is harvested with forced child labour, according to the U.S. government; and which a large chunk of the clothing industry has banned from its supply chains.

Nice work if you can get it. And if you can't, you can always force schoolchildren to do it.

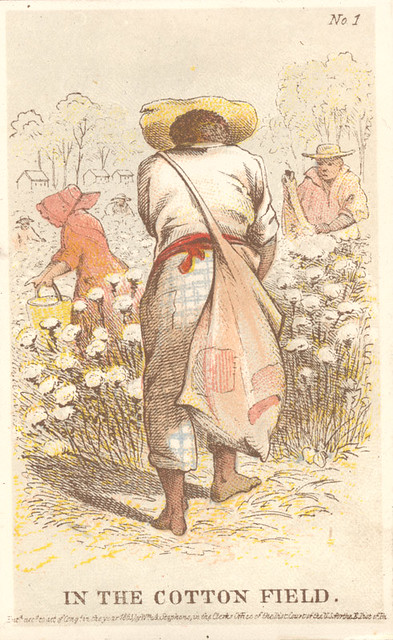

Top image: 'In the Cotton Field' (Civil War collecting card c. 1863), Library Company of Philadelphia/Flickr/Creative Commons