Guinea's opposition parties have worked hard to develop a unified political memory about what happened on the 28th September. Probably one of the reasons they remain within a unified coalition is because they and their supporters share the experience and solidarity of the repression on that day; and it'll be significant to see what happens to the Forces Vives once it comes to election-time.

But interestingly, that shared memory has been formed not just by the opposition parties' statements, or even by people sharing stories and experiences personally, but by a rapidly-circulated body of photographs and video clips of the events at the stadium. The government junta's claims about what happened that day - a 'violent' demonstration, police threatened, crowd members carrying their own firearms who fired on the police, soldiers staying in their barracks and only a small number of people killed after a stampede - were immediately falsified by film clips and photos: of soldiers firing on demonstrators, public rapes and piled-up bodies. Almost all were taken on people's mobile phones, and almost everyone in Conakry has seen them - in a country where relatively few ordinary people have regular access to the internet, or their own email addresses.

People haven't seen the footage on Youtube or Facebook or viral emails - it seems to have been circulated almost entirely on people's mobile phones themselves. The first thing that the first young person I interviewed said was 'Tu as le Bluetooth?'

28 Septembre CD-ROMs and DVDs are also selling in Conakry's markets, and showing in the tiny shack-cinemas throughout the city where people usually go to watch a big European football match, or play on a Playstation for an hour.

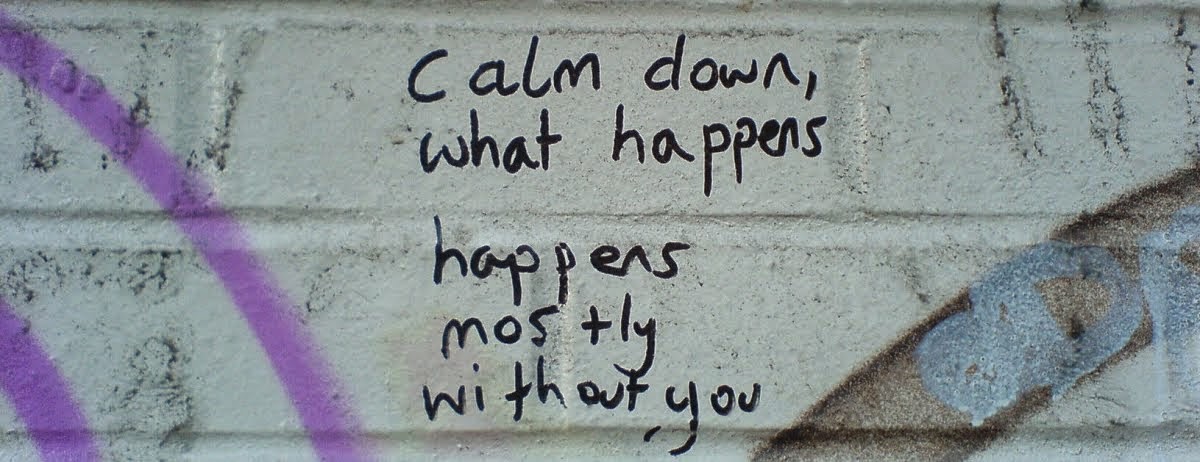

I know the impact of social technology is continually over-hyped. And it's obvious that international pressure - particularly from ECOWAS and France - has to a large extent shaped the CNDD's more moderate posture in recent weeks. But I don't think the impact of this corpus of visual imagery can be underplayed in what's subsequently happened in Guinea; the opposition parties growing in strength, and the CNDD having finally to appear, at least, to cede some power. Effectively, cameraphones have ensured that there's simply no way anyone in Guinea can believe that the regime's story about the repression is true, even if those images themselves select another particular version of events. Despite relative popularity immediately after coming to power, the CNDD are now literally unsupported.

The first widely marketed cameraphones appeared in the global North around 2003; and we've just reached the stage where enough people in rich countries have got rid of their first cameraphones for them to be fairly widely available throughout east and west Africa. Visual sousveillance has finally reached even the poorest parts of the global South; and, to some extent, seems to be working to shape remembering and forgetting. And I'm glad that no amount of fresh paint is going to stop that.