So. Johnnie Walker-loving mass murderer Kim Jong-il may be dying. Although it's obviously difficult to tell - he was apparently dying from a stroke in 2008. And from fatal pancreatic cancer in 2009. He's such a tease.

The real question, of course, is whether it's actually going to make any difference if the loveable little Nork-knome kicks it? Media coverage of the Democratic People's Republic seems to suffer more acutely than that of any other country from 'dictatoritis': the implausible belief that the intractability of an international crisis is entirely due to the fact that a single uncompromising psychopath has, despite the political handicap of judgement-obscuring mental illness, somehow managed to seize and maintain control of an entire nation. Just displace Kim and his unhinged family, goes this line of argument, and a new dawn rises over Pyongyang. And while we've all learned to love to hate Bashir, Saddam, Uncle Bob, nowhere has international strategy bought into a dictator's own personality myth as completely as in the case of North Korea.

It seems to be North Korea's 'crime as foreign policy' that encourages the Team America theory of Korean IR. The ballistic missile proliferation. The mass currency forgery. The dodgy Ilyushins laden with weapons on their way to Iran. They all make it easier to think of North Korea as a country captured by a single mad criminal family. In fact, states captured by mafias and crime dynasties (rather than wider elites) seem to tend to be weak states with a lot of ungoverned political space (think central Asia), not highly controlled autocracies like North Korea. Why shouldn't we see the Korean situation instead as something much more common: a state with a corrupt but comprehensive government apparatus, a predictably self-interested elite, locked like others into an intractable but familiar strategic deadlock with a militarily competitive neighbour?

Ballistic missile testing is a case in point. When the Norks test a missile, as in 2009, the Security Council does a Chapter VII nut. Quite right too. It's not often remarked, though, that South Korea also likes ballistic missiles. Enough to have a clandestine procurement programme. It's just that no-one talks about it like that, because it's called a 'civilian space programme', and it does ostensibly useful things like launching 'satellites for climate change research' (so that's all right then). Everyone's very sympathetic when South Korean ballistic missile (sorry, satellite launch vehicle) tests blow up. As in June this year, when South Korea's KSLV-1 rocket exploded moments after take-off. How did the BBC report it?

South Korea's first launch of the two-stage KSLV-1, in August last year, failed to place its satellite payload into the proper orbit.

Four months previously, an attempted space launch by North Korea was deemed to have failed when the US reported that both rocket stages had fallen into the Pacific Ocean.

The North's launch was seen as a cover for a long-range missile test, and prompted UN sanctions.

Pyongyang had voiced irritation at the South's rocket development, but most other powers in the region accepted that its attempt was part of a peaceful civilian programme.

But space rockets are, um, ballistic missiles. Few space programmes are purely civilian or commercial. Even if they genuinely have civilian objectives, they're always developing countries' ability to launch warheads too. Is it any wonder that North Korea gets a bit priapic (and vice-versa, of course)?

Interestingly, as everyone was comiserating earlier this year about South Korea's rocket test failure, a little-reported Florida court case opened an interesting window into South Korea's space programme. It's a grubbily instructive little tale.

According to the court papers: Juwhan Yun, a South-Korean-born naturalised US citizen running a New Jersey-registered company called Blue Hill Corporation, was arrested in April 2009. In May 2010 he finally entered a guilty plea, admitting to brokering a series of illegal arms deals - illegal because Blue Hill Corporation was completely unregistered as an arms broker. Yun had apparently acted for the Korean government to procure everything from Nike missile components, Russian Sukhoi-27 fighter jets, and US-made F-5 and F-16 parts, to an 'RD-180 propulsion system', also from Russia. According to correspondence between Yun and a confidential informant quoted in the investigating agent's affidavit, the RD-180 propulsion system was intended for the KSLV-2, the successor rocket to the KSLV-1 'climate change research satellite' launch rocket that failed this year. Yen apparently told the informant's company that Russia had recently refused to sell the RD-180 rocket engines to South Korea.

While insisting he wanted to do 'legitimate business', Yun appears to have been trying to make arrangements for technology transfer to South Korea in spite of the Russian refusal: leveraging the informant's Russian contacts to obtain RD-180 manuals and technical documentation from Russia, and then trying to find a "retired expert/specialist with much experience at the right job" - apparently approaching a scientist at the University of Central Florida's Aerospace Program - to teach the South Koreans how to nativise the RD-180 rocket engines.

In his post-arrest statements Jun stated that he was working for a "subcontractor for the KSLV programme". The company isn't named in the court papers, but we are coyly told that "a check of public source information via the internet verified that the company identified by Yun is listed as a member of the Korea Defense Industry Association and was previously involved in the Altitude and Orbit Control Subsystem and the Propulsion Subsystem development for the Korean KOMPSAT-1 satellite." It doesn't exactly require a super-sleuth to repeat the googling. Which company? Well I wouldn't want to libel anyone, but, um, think of one of South Korea's largest conglomerates, rhyming with "Whanwha".

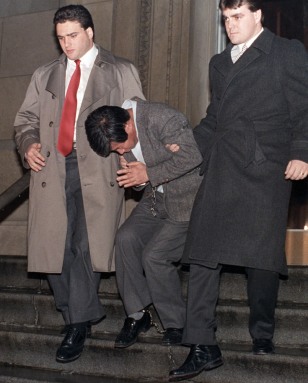

If Yun was telling the truth, then it's nice that South Korea's leading industrialists, and its government, were still doing business with him. Because he has some serious form: here he is in 1989,

just after being sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison (and barred permanently from the US arms brokering register) for yet more illegal arms trading. This first time round, Yun had similarly set up shop in the US to buy munitions for South Korea, and ended up acting as an agent for a South Korean trading company while negotiating with a notorious UK arms dealer to buy bombs filled with Sarin nerve gas that Yun told his contacts were for sale to Iran (the deal never went through).

Hmmm. Clandestine ballistic missile procurement? Government-linked arms procurers trying to flog nerve gas to Iran on the side? Which Korea would that be then?

I'm not trying to equate North Korea with South Korea. For instance, the South Korean government doesn't like human rights very much, but it's yet to preside over the starvation of several millions of its citizens.

Nor are South Korea's government, companies or agents unusually dodgy. The point is simply that all governments under military and strategic pressure get involved in this kind of dodgy stuff. The Korean stand-off is a conflict like many others, with aggression, clandestinity and strategic deadlock on both sides. Its resolution, equally, is likely to require political movement on both sides - compromise, not a lucky bout of pancreatic cancer.